Written By Gabrielle Powell

A museum may be offered an unparalleled, exceptionally significant object that would automatically become a collection highlight and attract many visitors to the museum to learn about an important part of history and culture. But there is always something that will immediately stop a museum staff member from accepting this type of object – and that is provenance. Provenance is an often complex and challenging topic for museums, particularly for ancient history collections. Strict legal and ethical requirements govern the way museums should collect objects, and this sometimes results in refusing an object for acquisition due to a lack of provenance documentation.

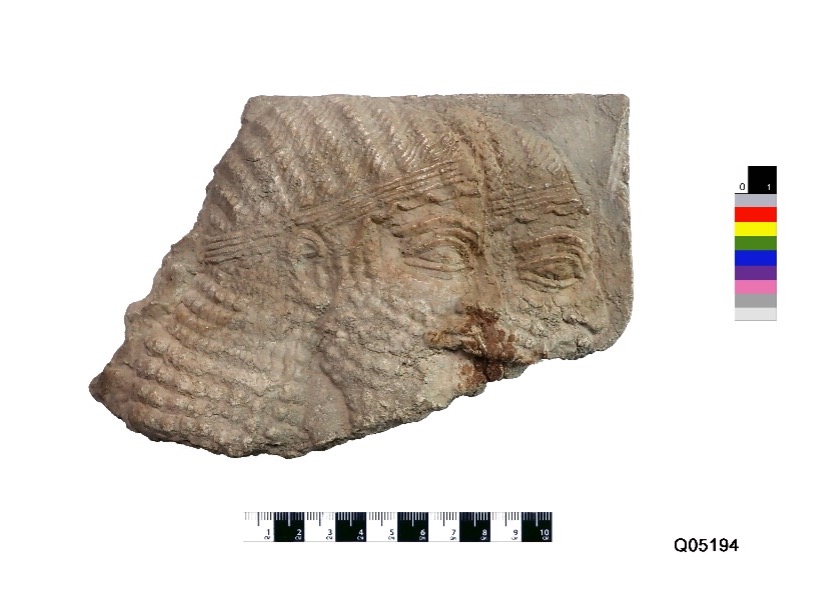

In 2021, the Abbey Museum acquired a Neo-Assyrian relief fragment from a donor. The relief fragment is believed to be from the archaeological site of Nineveh, located in Northern Iraq. Its artistic style points us to believe it is from King Ashurbanipal’s North Palace in Nineveh. The fragment features two overlapping bearded figures wearing a four-roped headband. These figures are potentially spearmen or guards, perhaps originally positioned next to the King or other important officials before it was cut and separated. Last year, I reached out to the Abbey Museum to see if they had any potential objects in their collection that could be used as a case study for my Museum Studies dissertation. The staff put forth the idea of researching the provenance history of the Nineveh fragment as it was missing some of these details. I was quick to accept, as provenance is a fascinating topic in the museum world and is something I am quite passionate about.

Defining Provenance

I should firstly break down what the term provenance means as it is often not fully understood, even among those who work in the field. With the help of Rosemary Joyce’s (2012) book chapter, From Place to Place: Provenience, Provenance, and Archaeology, I define provenance as the ownership and whereabouts history of an object from the moment of its creation. A similar, yet different term, is provenience. Provenience is the specific location of where an object was found or excavated. Provenience (or findspot) is one element of an object’s provenance but does not capture the full story. It is the full provenance history that allows for an object possess a greater sense of historical and social context. Among other things, provenance provides us with information about where an object would have been specifically used in ancient times, how the object moved from its excavation area to other parts of the world, how its value changed throughout history (monetarily, aesthetically etc.) and whether it has been physically altered, restored or even if it is potentially a fake.

The Important of Provenance

Provenance is an ever-present and challenging aspect of museum collecting. Reckless collecting practices from museums, dealers, and individuals throughout history has meant the objects in museums today are often lacking in provenance documentation. You may think, why do we even need this documentation and what purpose does it serve? Surely possessing the object itself is enough to construct its meaning and value? Not quite . . . provenance has proven to be a crucial element of an object’s existence. The antiquities market is immense, powerful, and entangled with illegal and unethical practices. Conflict in the Middle East has resulted in an overwhelmingly large portion of Mesopotamian artefacts being caught up in illegal activity, such as clandestine excavations, looting, and theft. Furthermore, the desire for these types of objects from market nations such as the U.S and U.K has meant that there are a large number of fakes and forgeries intertwined with these authentic objects. This is why provenance is so crucial. If an object has valid provenance documentation which shows that it has not been involved with any illegal or unethical activity, the museum can feel safe and certain in their decision to acquire the object. If a museum accepts an object without this provenance documentation, it is difficult to know whether it has been caught up with this kind of activity and the museum could be inadvertently supporting illegal and unethical practices by acquiring and displaying it.

Tracing the Provenance of the Assyrian Relief Fragment

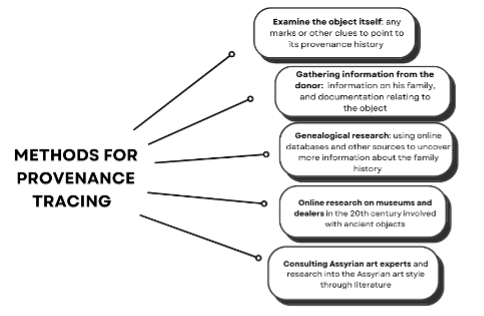

Part of my dissertation research was to uncover more provenance information on the relief fragment the Abbey Museum acquired. This process of provenance tracing is unique to each object, as each object and its context it different. The process often requires an investigate approach – like a museum detective searching for clues in all sorts of different places. The first step involved gathering as much information from the donor and working back through the family history to reveal where and how the object entered the family collection. Then, it was researching online databases, museum archives, antique dealer catalogues, and other sorts of correspondence to attempt to find connections.

Information as to when and where the object was brought into the donor’s family collection was revealed – it is believed that the donor’s relative bought the object in England around the late 1940s or early 1950s. The donor said his relative bought the fragment from a “closing down museum”, yet exactly what/where this museum this was, is still unknown. The dispersal of museum collections post World War 2 was quite common due to a lack of resources to continue museum operation. This made the investigation quite challenging due to its wide scope. There’s still much that remains unknown about the object, such as how and when the object moved from Iraq to England, and whether we can be certain that it is authentic. Assistance from an Assyrian art expert would be beneficial, as would more online research on musuem collection dispersals in the U.K during the 20th century. Although not a complete success, my research did provide some clues relating to its history as well as some more avenues to explore. The lack of information uncovered is not something that is uncommon as provenance tracing is a long process that requires a large amount of time and resources.

The future of Provenance Tracing in the Museum World

Museums must be transparent to the public about provenance issues in order to raise public awareness and strengthen the protection of cultural heritage. Museums must be committed to the objective of deconstructing historical authority and allowing for an openness between visitor and institution. I therefore, applaud the Abbey Museum for allowing me to research this object and share my findings with others.

The often complex and intertwined problem of provenance has perhaps thwarted museums from attempting to clearly relay information about provenance to the public. However, it is a crucial mechanism in the protection of cultural heritage, both for the objects and their communities. TV shows such as Stuff the British Stole on ABC has increased public awareness on this topic and will hopefully provide people with the knowledge and confidence to question what is displayed in a museum. Furthermore, our digital world has allowed the process of provenance tracing to become somewhat easier due to the accessibility of a range of records and archives from around the world. As more and more documents and objects become digitised, the more provenance information can be uncovered.

This increase in transparency will also allow more criticising visitors to understand that not every object in a museum is stolen, and not every object is connected to illicit trading. Rather, that every object in a museum has its own individual story that warrants a thorough investigation to safeguard the object and those who are connected to it. Cultural heritage is crucial for human welfare and survival, and we must dedicate our time and resources into its protection for future generations.

The Abbey Museum would like to acknowledge Gabrielle for her support in delivering this article and her expertise to our collection.