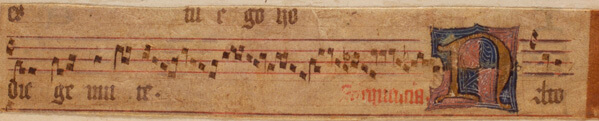

As visitors wander through the Abbey Museum they come across the entrance to a side gallery. Dimly lit, a figure of an old monk sitting in the corner, silently scribing a biblical text, beckons the visitors in. As they near the doorway case lights flicker on to reveal a treasure room of medieval manuscripts. The oldest manuscripts include an antiphon fragment dating from the 1100 AD. It contains a musical response and text for the third nocturne of matins.

One of my favourite medieval manuscripts to share with visitors is a folio from a Book of Hours. Dated to 1450 AD, it is written in ink on vellum and illuminated in paint and gold leaf. What is so compelling about this piece is a tiny illustration of a bird feeding her chicks in the nest which is incorporated into one of the illuminated capital letters. There is also an example of the rules from a monastic order from Italy that dates to 1500 AD, and a 1751 Venetian illuminated charter which confers freedom of an Italian city on the mercenary soldier, John Antonio Crotta.

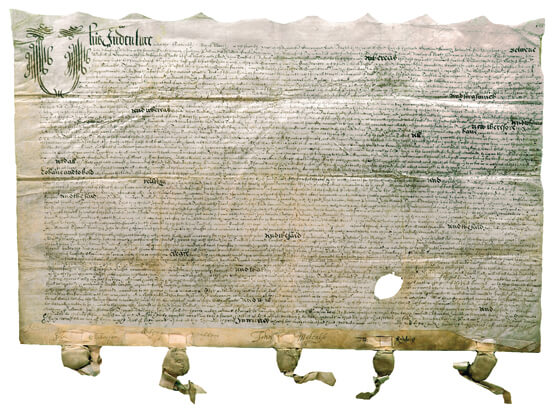

Our medieval manuscript gallery also contains part of a remarkable collection of documents that hold the history of two bickering families, the Tunstalls and Thompsons, who come from the Yorkshire Dales, centred on the village of Aysgarth. Known as the Aysgarth Documents, they consists of over 60 items including a number of indentures, wills, inventories and a letter that span nearly 400 years of English history, from the great enclosures after the Civil War to the clearances that led to the mass migrations of rural people to the new colonies of Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The oldest of these documents is a 1626 AD ecclesiastic manuscript written in Latin which offers support of the archdeacon, Edward Mainwaring, to the recently windowed Joan Tunstall and her children. But one of the most moving is an excommunication by the Established Church of an Anne Tunstall who bravely became a Quaker, and forfeited nearly two thirds of her meagre income to keep her faith in a little meeting house high on the dales.

DNA from Medieval Manuscripts reveal Britain’s agricultural past

The content of these manuscripts give archaeologists and historians amazing insights into the social experience of those referred to in the documents. A recent article written by Ben Miller explains how samples of DNA from manuscript parchment are being used to recreate the agricultural history of a specific area.

A team of researchers from the University of York and Trinity College Dublin have established the breeds of animals used to create specific parchments. They have identified black-faced breeds such as Swaledale, Rough Fell and Scottish Blackface were common during the 18th century.

“Wool was essentially the oil of times gone by,” says Daniel Brady, a Professor of Population Genetics who helped the European Research Council-funded research.

“Knowing how human change affected the genetics of sheep through the ages can tell us a huge amount about how agricultural practices evolved.”

Although our manuscripts may never come under such detailed research scrutiny, it would nevertheless be interesting to know what secrets they still have to reveal.

The Abbey Museum is open Monday to Saturday from 10 am – 4 pm if you would like to come and view our wonderful manuscript collection.