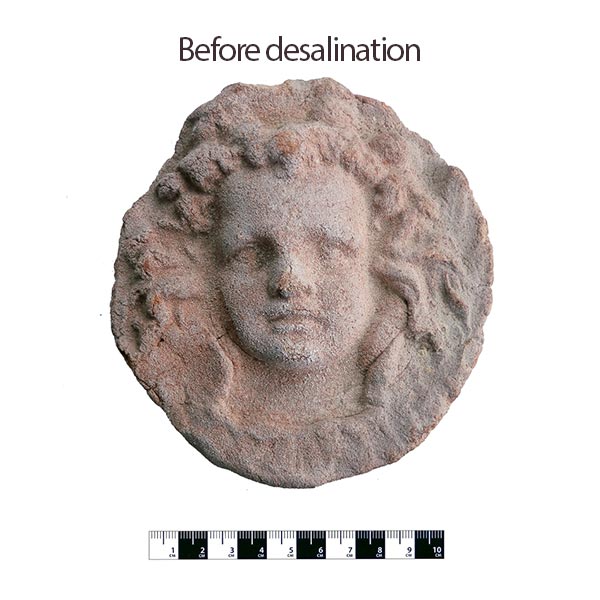

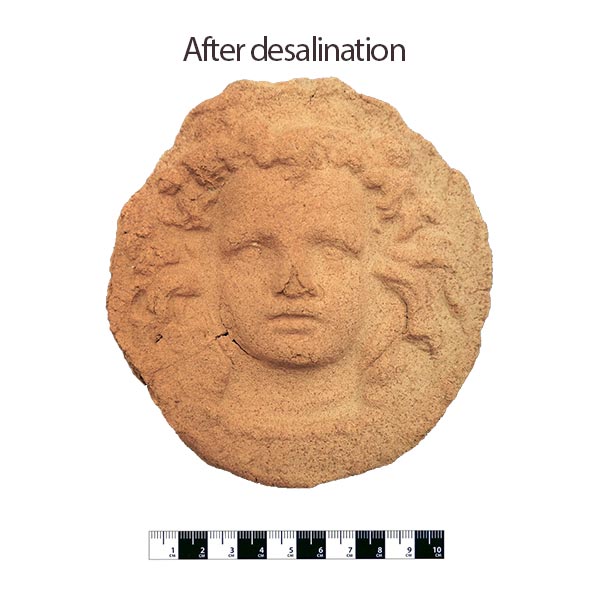

Salt can have devastating effects on ancient artefacts. It also can be a tricky process to deal with these salts to protect an artefact over time. Such is the case with one particular process taken on an artefact in the Abbey Museum Collection, the circular plaque of Apollo.

We got on a call with Holly Jones-Amin to take us through the process. She is undertaking a PhD at the University of Monash, and is a Senior Conservator at The University of Melbourne where she manages the objects consultancy laboratory. Holly has specialist skills in the treatment of archaeological and ethnographic materials.

Abbey Museum: How does the story of salts within an artefact begin?

Holly Jones-Amin: The story can go back to either manufacture or it can go back to use. Some pottery, or some clay objects, are made with the addition of salt. If it’s a utilitarian object, such as a cooking vessel they have some salt present from use and therefore it’s integral to the object’s story. With the tablets they’re never fired, by firing an object you’re closing the pores in the object and therefore you’re making it less porous. The highest degree of pottery not being porous is porcelain, the lowest degree is not being fired at all, and not far from that is something like a 5,000 year old ceramic that’s been fired in a bonfire.

The object has either been purposefully put in a tomb, or it’s been purposefully buried, or it’s been discarded.

“With the roman tablet – there’s cracks and surface loss on the object – and that’s from the salts because they move to the surface and as they get closer to the surface they push harder and harder until you get to the point where it starts flaking.”

– Holly Jones-Amin

So what happens to these artefact underground?

Whatever goes through the soil goes through the object. Because the object is porous, the water goes through the objects so the object is changed by deposition. By being changed it takes on the salts…the salts themselves are going to be what’s in the ground, they could be nitrates, they could be chlorides, it could be what’s present naturally, it could be added through farming activity.

When the object comes out of that environment, and it could be something that happens immediately or something that happens much further down the track which is the case with the roman tablet, the salts dry out if they’re in a different level of humidity. When they dry out they go back from being something that’s soluble to something that is dry and when it dries it becomes much bigger than it was…it puts a lot of force on the object, and it can cause the surface of the object to come off.

…You start to lose what’s important to the surface of the object, the decoration, the diagnostic features that make that object so. With the roman tablet – there’s cracks and surface loss on the object – and that’s from the salts because they move to the surface and as they get closer to the surface they push harder and harder until you get to the point where it starts flaking.

How do you get rid of these salts?

There’s several things you can do – one is that you don’t do anything but control the humidity (in the space) the object’s in and that’s the most positive thing you can do. However, it’s hard to do because you have to understand which salts are present, which means you need analysis and then you need to be keeping the object at that level of humidity – so there needs to be some moisture to stop the salt from drying out.

Most typically what’s done is that we desalinate it. That could be done one of two ways – either immersing the object in water so that the salts move from the object into the water and you change the water and you measure the level of salt – which is a conductivity reading of the water and you keep doing that until you get to a point where you’re not removing salts anymore, all you’re finding is very little difference from one change of water to the next. Typically you would change the water once every week when you’re doing that (this is the process used in the circular plaque of Apollo).

Another way that it could be done when the object is to big or too dense or you’re too concerned about the surface is you can actually do desalination by poulticing the surface – so a little bit like a woman putting a face mask on – so you’re drawing the material into the poultice – the poultice is usually paper pulp.

Check out Grimwade Conservation on Instagram @grimwadeconservation

©Abbey Museum 2020